Ephesus Information

According to renowned ancient writers Strabon and Pausanias, Ephesus was originally established by the Amazons on lands predominantly inhabited by Cariean and Lelegean tribes. The city was named after an Amazonian queen.

During the 1040s BC, the western Anatolian coastal regions, including Ephesus, lacked unity among the native population, including language. As a result, Ephesus became a Greek colony in the 10th century BC.

According to early accounts, the foundation of Ephesus is attributed to Androclos, the son of Kodros, the king of Athens. Androclos and his companions sought guidance from the oracle of Delphi on where to establish their new settlement in Anatolia. The oracle’s response indicated that the location would be revealed by a fish and a boar. After a long journey, they arrived at the banks of the river Kaistros (modern-day Kucuk Menderes). While cooking the fish they caught, a frying fish leaped out of the pan, igniting the dry bushes. A boar emerged from the burning bushes, and Androclos chased, caught, and killed it. Convinced that the oracle’s prediction had come true, Androclos and his companions founded their new city at the foot of Mount Coressos (today’s Panayir Dagi). Androclos and the Ionians lived in the city they had built for 44 years.

Despite surviving an attack by the Cimmerians in the 7th century BC, Ephesus recovered and gained fame for its scientific advancements, techniques, and wealth. Much of its reputation stemmed from the renowned Temple of Artemis, one of the Seven Wonders of the World. Later, Ephesus came under Persian rule. In the 5th century BC, following the death of the Persian king Cyrus, the dissatisfied people of the Ionian cities rebelled against Persian rule in what became known as the “Ionian revolt.” Ephesus played a significant role in the uprising. The revolt concluded in 494 BC with the defeat of the Ionian army.

During the 3rd century BC, Alexander the Great ruled over Europe and Greece. He aimed to drive the Persians out of Asia Minor and establish unity. Together with the Ionians, Alexander participated in the historic “horseman’s battle,” which altered the course of early history. In 334 BC, Alexander entered Ephesus, encountering no resistance as the Persians had fled. He dismantled the oligarchy and proclaimed the establishment of people’s sovereignty. This period marked the golden age in Ephesus’ history. With a population of 300,000, the city held immense power and wealth in the Near East, greatly influenced by the divine presence of the Temple of Artemis. After Alexander’s death, Ephesus came under the rule of Lysimachus, one of his generals, who oversaw the construction of the city walls that still stand today. In 130 BC, Asia Minor, including Ephesus, was annexed by the Roman Empire. During the reign of Augustus, the most glorious era of the Roman Empire, Ephesus was declared the capital of the province, surpassing Pergamon and becoming the largest and foremost metropolis in the region. This further solidified Ephesus’ status as a prominent trading center, and its population exceeded 200,000. Many of the remains visible in Ephesus today date back to the time of Emperor Augustus.

In 262 AD, Ephesus suffered a devastating assault by the Goths, resulting in the city’s destruction. The magnificent Temple of Artemis was plundered. Following this attack, Ephesus never fully recovered its former power and splendor. In the subsequent centuries, a new religion emerged in Ephesus—Christianity. It rapidly gained popularity, eventually replacing the worship of the traditional goddess Artemis. In this new era, the first church in history was established in Ephesus, dedicated to the Virgin Mary.

The assault by the Goths in 262 AD left Ephesus in ruins. The grand Temple of Artemis was looted and devastated. Unfortunately, Ephesus never managed to regain its former glory and influence. However, the early centuries AD witnessed the rise of Christianity within the city, marking a significant transition in its religious and cultural landscape. The prominence of Ephesus as a center of worship shifted from the ancient deity Artemis to the veneration of the Virgin Mary.

Overall, Ephesus holds a rich historical legacy, from its origins as a Greek colony and its association with legendary figures like Androclos, to its thriving period under Alexander the Great and subsequent Roman rule. While it may have suffered setbacks and destruction throughout its history, Ephesus continues to captivate visitors with its impressive archaeological remains, offering glimpses into its past as a vibrant center of civilization and spirituality.

The Temple of Artemis

The origins of the Ephesian Artemis can be traced back to the ancient Anatolian “mother goddess,” making her the oldest deity of the region. Throughout history, Artemis underwent various transformations influenced by different cults before assuming the form of Artemis Ephesian. The temple dedicated to this Ephesian Artemis, who replaced the ancient Anatolian goddess, was renowned as one of the Seven Wonders of the World in ancient times.

During the golden age of Ephesus in the 6th century BC, the city experienced significant development. The construction of the grand temple was entrusted to an architect from Samos. To stabilize the marshy ground on which the structure was to be built, the architect used coal dust beneath the foundations. The temple stood as the largest structure of its time, measuring approximately 220 by 425 feet and boasting 127 columns. Additionally, historian Pliny the Elder noted that the 36 columns in the front were adorned with decorative reliefs. The temple was surrounded by rows of columns, with 8 columns on the western side and 9 columns on the eastern side.

Within the temple, the cult statue of Artemis was positioned in a space referred to as a “Saikos” or possibly a “Laikos,” resembling an open-air courtyard. A similar architectural plan can be observed at the Temple of Apollo in Didyma. Tragically, the magnificent temple was engulfed in flames on the night Alexander the Great was born in 356 BC. The arson was committed by a mentally unstable man named Herastratos, who sought to gain a place in history. The wooden roof, constructed with cedar beams, caught fire rapidly, leading to the collapse of the entire temple. Soon after the destruction of the archaic temple, construction of a new one began on the same site and foundation.

Strabo, in his book “Geography,” mentioned that this renowned temple was destroyed and rebuilt seven times. According to Strabo, when Alexander the Great expressed his intention to finance the reconstruction of the temple, the Ephesians responded, “A god does not build a temple for another god.” In front of the temple, there was a U-shaped, angular altar, accompanied by two rows of 92 slender Ionian columns. At the rear corners, statues of a four-horse-drawn chariot were placed, with one of the horses now exhibited at the Ephesus Museum. The British Museum houses a relief on one of the column bases, depicting the tragic scene of Alcestis, who volunteered to be sacrificed to save the life of her husband as she was being taken away for execution.

Originally situated by the seaside, the temple gradually sank into obscurity as the river Kaistros (Kucuk Menderes) brought sediments that filled the sea. Today, the temple’s location is approximately 5 km inland from the city.

The State Agora

Upon entering the ancient city of Ephesus through the Magnesia gate, one is greeted by the expansive State Agora, measuring 160 by 56 meters, accompanied by a cluster of interconnected structures. At the heart of this agora once stood a rectangular temple, whose architectural elements influenced the construction of later edifices. This temple, along with the surrounding agora, dates back to the first century BC. However, it was during the reign of Emperor Theodosius (379-395 AD) that additional structures were added, giving the agora its final form.

During the late Roman period, columns adorned with Corinthian capitals were erected, modifying and supporting the structure. Notably, the presence of a basilica in front of the “Prytaneion,” where state affairs were deliberated, suggests that the building had evolved over time into a venue for city meetings and court sessions. Located north of the basilica, the “Various Bath” is believed to have been a private bath commissioned by Flavius Domianus. Throughout the Roman Empire and the Byzantine era, the structure underwent alterations and expansions. It was constructed on the leveled terrain at the base of Mount Panayir, utilizing large limestone blocks for its walls and brickwork for the roofing. Remarkably, traces of the underground hot air pipes can still be observed today.

Odeion

The Odeion, a remarkable structure, was constructed approximately 150 years AD, as revealed by the inscriptions discovered. It was commissioned by Publius Vedius Antonius and his wife Flavia Papiana, esteemed members of Ephesus’ illustrious family. The inscription suggests that the Odeion served dual purposes, functioning as both a concert hall and a council chamber. Impressive in its design, the Odeion featured 23 tiers of seating, providing accommodation for up to 1400 spectators.

The Prytaneion

The structure located at the western end of the basilica dates back to the 3rd century BC, and its final form took shape during the reign of Emperor Augustus. This prominent site served as a hub for political discussions, religious ceremonies, and festive gatherings. Behind it stood a covered hall, while the courtyard boasted mosaic paving adorned with intricate designs featuring Amazon shields and passion flowers. During excavations at the Skolastikia baths in the year 400 AD, two statues of Artemis were unearthed and are currently showcased in the Ephesus museum.

To the west of the Odeion, there existed a captivating sight—a columned portico encircling the temples dedicated to the imperial cult. These temples, although relatively small in size, presented a grandeur of their own with four columns adorning their eastern facade.

The Domitian Suare and The Pollio Fountain

In the 4th century AD, a round pedestal adorned with garlands was brought from another location and placed here. Additionally, a triangular fragment featuring a relief of the goddess Nike is a part of the Heracles gate. As you enter the Domitian Square, you can observe the remains of a monumental gate on both sides of the street. One of the remarkable structures in this area is the Pollio Fountain. Situated on the side of the state agora facing the Domitian Square, it boasts a wide and tall arch, exuding magnificence. Water used to flow into the pool in front of it through a semicircular exedra. Along the circular edge of the pool, there once stood the statue of Odysseus. Some parts of this statue are now exhibited in the Ephesus Museum.

The Temple of Domitian

Ascending from the Flavius lineage, Domitian assumed the role of emperor in 81 AD. Initially known for his fair and just governance, his rule gradually took on a despotic nature, eventually culminating in him declaring himself as the “master and god.” The discovery of a colossal statue of Emperor Domitian, including its head and arm, provided evidence that the temple was dedicated to him. On the temple’s front side, facing the square, a series of well-preserved storerooms can be found.

In the Ephesus museum, there is a section of an altar belonging to the Domitian temple, which exhibits exquisite craftsmanship. The base of the altar was constructed from limestone, while the upper part was made of marble. Elaborately carved blocks adorned with figures resembling soldiers wearing helmets can be seen above the niches. These figures represent Memmius, Domitian’s father Caius, and his grandfather Sulla.

The Curetes Street

The street originates from the Celsius Library and extends towards the junction of Mounts Panayir and Bulbul, sloping southeastward. It then leads to the State Agora and ultimately culminates at the Heracles Gate. This street, adorned with white marble slabs, serves as a grand thoroughfare where the city’s monumental structures are aligned. On both sides, there are columned galleries with decorative mosaic flooring. The spaces between the columns were embellished with statues of prominent individuals, with their pedestals still standing in their original positions. The street derives its name from a captivating mythological tale: while “Leto” was impregnated by “Zeus” and giving birth to “Artemis” in Ortygia, located southeast of Ephesus, the “Curetes,” semi-deities closely associated with Zeus, created a tumultuous uproar to prevent Hera, Zeus’s wife, from hearing the cries of the baby. This act ultimately saved Artemis’s life. The Curetes held great reverence as a priestly class in Ephesus. Their primary role involved reenacting the birth of Artemis in a dramatic annual ceremony held in Ortygia. Initially, the Curetes were solely affiliated with the Artemission. However, during the Roman Empire, they also gained a place in the Prytaneion and assumed the responsibility of maintaining the sacred fire of “Hestia.”

The Trajan Fountain

Based on an inscription found on a prominent cornice near the fountain, it is revealed that the construction took place between the years 102 and 114 AD, dedicated to Emperor Trajan. The fountain consisted of two tiers of columns arranged in a “U” shape, with an angular design. Within the central niche of the pool, there once stood a statue of Emperor Trajan, grand in size. Water flowed into the pool through a wide channel situated beneath the emperor’s statue. This fountain, known for its substantial size, underwent restoration and was carefully reinstated.

The Skolastikia Baths

Situated on Curetes Street, adjacent to the Fountain of Trajan, the Skolastikia Baths were the largest building of their kind in Ephesus. Originally constructed between the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, the baths underwent significant repairs and enhancements during the 400s AD under the supervision of Christian Skolastikia. The building, consisting of three stories, including the collapsed ground floor, featured two entrances. One entrance faced Curetes Street, while the other connected to the back street leading to the Grand Theater and palaces.

A small section of mosaic flooring, located near the eastern wall of the tepidarium, serves as a glimpse of the original floor covering within the baths. In the same complex as the Skolastikia Baths, dating back to the initial construction period in the 1st century AD, is the Latrina, which served as the public toilets of the city. The Latrina comprised a square pool and a row of stone commodes positioned along the bottom of the wall. Beneath the stone commodes, there existed a deep partition for waste disposal, connected to a well-developed sewage system. The roof, designed as eaves, only covered the toilet section and was supported by four columns placed at the corners of the central pool.

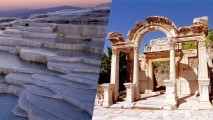

The Temple of Hadrian

This is one of the small but very attractive edifices on Curetes street consisting of a monumental Pronaos where a statue of emperor Hadrian used to stand in the past ,and a Naos. From the inscription on the architrave it is understood that the temple had been dedicated to emperor Hadrian. A bust relief of “Tyche“, goddess of the city, adorns the uppermost point in the center of the arch. The door leading to the main location of the temple is richly decorated with rows of lotus leaves. On the both sides of the upper lintel ever the door there is a frieze related with the legendary story on the founding of Ephesus, taken from another edifice during the first restoration in the 4th century, and a second group of friezes. In the first group a relief depicts scenes of gods and goddesses with Androclos, the founder of Ephesus, chasing the boar, gods with amazons and amazons a Dionysian processions.

Terrace Houses

These are exclusive residences situated on the slopes opposite the Temple of Hadrian along Curetes Street. Commonly known as the “rich houses,” they were uncovered during recent excavations. The houses near Curetes Street feature colonnaded porticoes, while step streets connected directly to the house entrances. Although multi-story, only the ground floors were used for daily activities, while the upper floors primarily served as bedrooms.

Water channels supplied running water to the houses, and some even had their own wells. The hot air from the baths, conveyed through earthenware pipes and vents, provided heating. Notably, the walls of these houses were adorned with frescoes. Older frescoes concealed beneath newer ones indicate that these houses date back to the 1st century AD. The frescoes generally depict animals, mythological themes, and scenes from daily life. The restoration of two houses has already been completed.

The first house, known as “House A,” is a two-story residence spanning 900 sq. m. It comprises 12 rooms and welcomes visitors through an arched doorway leading to a mosaic-floored hallway. The house boasts four columns and marble flooring. On the northern side, there is a dilapidated fountain amidst two rooms adorned with mosaic floors and frescoes. Adjacent to the peristyle lies a 4-meter-high hall, known as the “theater room,” featuring frescoes from the 2nd century AD. These frescoes depict scenes from Menander’s comedy “Skyonioi” and Euripides’ play “Orestes and Ephegenia.” The walls of the room showcase life-size semi-nude figures of men and women. On the northern wall, a depiction of the battle between “Heracles and Akheleos” is featured. The second house, known as “House B,” consists of two peristyles. In the center of the room, surrounded by six columns with Corinthian capitals, is a cistern with a marble lid, while a fountain adorns the southern end. Behind the fountain, two rooms with mosaic floors and frescoed walls can be found. To the east of the peristyle, there is a 4-meter-high hall adorned with black and white marble mosaics, serving as the owner’s resting place. The glass mosaics in the vaulted niche, believed to date back to the 5th century AD, depict the scene of “Ariadne and Dionysus” surrounded by birds. Additionally, scenes from “Poseidon and Nereid” are portrayed on the platform in front of it.

The second floor is accessed from the western corner of the aforementioned hall. The eastern room of the two rooms opening into the hall, adjacent to the peristyle, showcases depictions of standing “Muses.” The larger northern room serves as the dining room, featuring a floor adorned with coarse-grained mosaics. From a small kitchen on the western side, decorated with fish motifs on the walls, a passage leads to the second peristyle. The wall frescoes provide evidence that they were initially painted in the first century and underwent multiple repairs until the fourth century AD.

The Brothel

Situated alongside the Skolastikia baths, this structure forms a cohesive complex behind the temple of Hadrian and the Byzantine Stoa.

Originally designed as a two-story peristyle house, reminiscent of the residences on the slopes, the building has undergone several restoration projects, indicating intermittent usage from the time of Emperor Trojan until the 7th century. The central chamber, adorned with mosaic flooring, served as a gathering space for both leisure and dining. Adjacent to this room in the western section lies a bath, belonging to a separate house, embellished with its own mosaic designs.

The Celsus Library

The Celsus Library, situated at the intersection of Curetes Street and the Marble Road, stands as one of the most remarkable monumental structures in Ephesus. Reflecting the architectural style of Emperor Hadrian’s era, this building was constructed as a mausoleum for Jelius Celsus Polemanus, the proconsul of the Asian province, by his son Tiberius Julius Aquila. Aquila, who served as the proconsul from 105 to 107, intended to honor his father’s memory after his passing at the age of 70. Although Aquila himself passed away before the completion of the project, his heirs finished the construction in 135 AD according to his wishes.

The library’s facade features two stories, while its interior consists of a spacious single hall. To access the first story, one must ascend nine steps leading to a podium. The facade is adorned with four pairs of columns, and three entrance doors are positioned between them. The central door stands wider and taller than the other two. Within the niches between these doors, replicas of the original statues reside, symbolizing the virtues of Celsus in the following order: Sophia (Wisdom), Episteme (Knowledge), Ennoia (Destiny), and Arete (Intelligence). The facade exhibits a remarkable wealth of architectural ornamentation, creating a grand and monumental appearance. During excavations in 1904, when the sarcophagus was opened, the skeletal remains of Celsus were discovered in another lead coffin. Interestingly, despite suffering damage to its interior during the Gothic invasions in 262 AD, the library’s facade remained intact.

The initial restoration efforts for the library, which was found in a ruined state during the 1904 excavations, began in 1970 under the guidance of archaeologist W.M. Strocka and architect F. Hueber. Subsequently, in 1978, the facade underwent a complete restoration by the Austrian Archaeological Institute.

The Mazeus-Mitridates Gates and the Agora

Adjacent to the Celsus Library stands a triumphal arch in the Greek-Roman style. This arch marks the southeastern entrance to the commercial agora, believed to have been constructed in the 4th or 3rd century BC. An inscription in both Latin and Hellenic languages, consisting of gold-plated bronze letters (only the holes remain today), reveals that the gate was erected by Mazeus and Mithridates. These two slaves were granted freedom by Agrippa and dedicated the gate to Emperor Augustus, his wife Livia, and his late son-in-law Agrippa.

The gate features a three-sectioned attic, supported by robust pilasters of three arched passages, adorned with lavish decorations. The central passage is recessed, enhancing the architectural depth and giving the gate a regal appearance when combined with the attic walls. Surrounding the agora on all three sides were rows of storage rooms with vaulted roofs. The southern and eastern sides had two-story structures, while in front of all the storerooms stood covered porticoes supported by columns.

During recent excavations, some artifacts and remnants from the original Hellenistic-era agora were discovered, providing insights into the initial construction of this historical site.

The Marble Road

The Marble Road, originally known as the sacred way, had its origins at the Artemision and initially led to the Vedius gymnasium. It then continued its path between the grand theater and the agora, heading towards the Celsus library. From there, it turned eastward, passing through the Magnesia gate and eventually reaching Artemision again from the north. This road served as the main thoroughfare in Ephesus, encircling the slopes of Mount Coressos, also known as Panayir Dagi.

A notable section of the Marble Road, located between the Celsus Library and the Grand Theater, was paved with white marble slabs by a Roman named Eutrophios. As a result, it gained the name “marble road” that is used today. The central part of the road was elevated and sloped towards the sides, with a sewage line running underneath. Along the way, there was a Doric Stoa built on a high wall during the reign of Emperor Nero (54-68 AD), showcasing skilled stone masonry. This Stoa served as a passage to the agora, and a narrow colonnaded sidewalk led to the grand theater at the foot of Mount Coressos. These features date back to the late Roman Age.

Evidence, such as impressions of carriage wheels on the road pavements and the presence of narrow sidewalks, suggests that transportation along the Marble Road primarily relied on carriages. Many structures on the slopes of the mountains in the vicinity remain unexcavated, holding potential for further exploration. Notably, on the sidewalks of the road by the Stoa, one can find figures depicting a left foot pointing southward.

The Grand Theater

Originally constructed during the Hellenistic era, the grand theater in Ephesus underwent modifications during the Roman period. It was expanded under Emperor Claudius (41-54) and achieved its final form during the reign of Emperor Trajan (98-117). This remarkable structure, known as one of Ephesus’ most impressive edifices, played a significant role in the social and cultural life of the city, accommodating an audience of 24,000 in its auditorium. The theater’s most notable section is the scene, or stage building.

The surviving ground floor of the stage building, standing at a height of approximately 18 meters, showcases a grand and richly adorned appearance with its columns, niches, statues, and reliefs spread across three levels. A central hallway, running from north to south, houses eight rooms lined up side by side, leading to an entrance accessing the orchestra. During the classical period, theatrical plays were performed directly in the orchestra section. The stage building features five doors that open into the proscenium. The central door, larger than the others, serves as the main entrance with a niche above it housing a statue of the emperor. The special seats surrounding the orchestra were reserved for the esteemed citizens of Ephesus.

Spectators, upon purchasing their tickets in the form of lead coins, would reach their seats through two diazomas and two intersecting stairways leading towards the orchestra. All performers in the theater were male, adorned with masks and various costumes appropriate for their respective roles. Apart from theatrical performances, the theater also served as an arena during the 3rd and 4th centuries AD, hosting gladiatorial contests and animal fights.

The Harbour Street and Surrounding Structures

In front of the theater is a marble paved street that remained from the late Hellenistic period and meets the marble road in a right angle with one end reaching the harbor. This is the “harbor street of Ephesus, called also “the Arcadian“ according to the unearthed inscription the street was built and repaired by emperor Arcadius (395- 408 AD.) And named after him. It is 11 meters wide and approximately 600 meters long. This street, on both sides of which, at the same time, there were rows of stores with mosaic paved and colonnaded sidewalks in front of them, ended at the seaport with a monumental gate, called the ‘harbor gate’. Although a very small part of this complex has been unearthed to-date the structure is still very impressive with its few extant remains. The baths were built during the 2nd century AD. Close to the center of the street there are four monumental columns still upright with Corinthian capitals and decorated with niches at their bases. Statues, probably of the four evangelists, used to be on top of these columns dating back to the late brilliant period of Ephesus. People coming from overseas used to enter the city through this street, while the ‘royal road’ coming from Anatolia inland ended here. In the place of the large swampland found today, that came in to existence as a result of the daily deposited by the river Kasytros ‘Kucuk Menderes’ alluvium, was the busy port of Ephesus. Despite the various measures taken through the centuries, the action of the river menders couldn’t be stopped and the social and cultural life of Ephesus gradually died down with its port coming out of use. The excavation works carried out carried out in our days in the harbor area having reached down the strata of antique ages and with the various fins being unearthed shed light on our information about Ephesus.

Church of the Virgin Mary

The House of Virgin Mary, who is considered to be the holy mother of Christianity, is situated on mount Bulbul. Jesus Christ asked st. John, one of his disciples, to provide protection for his mother, Mary, before he died on the cross. It is believed that based on this, st. John Thought it unwise fort the virgin Mary this day in Jerusalem, so brought her with him to Ephesus. Here she remained hidden in a cottage, surrounded by dense trees, on the outskirts of mount Bulbul. The Virgin Mary remained there until she passed away. The most significant particularity about the fact that it was the first church built in the Asian province in dedication to the Virgin Mary. The ecumenical council which met in the year 325 in Izmit, introduced the trinity system of belief consisting of father, son and holy spirit. But this system of belief raised the issue as to how the divine and human properties of Jesus were separate, but the human ones prevailed. Cyril, the patriarch of Alexandria and pope Coelestius opposed this view. To end the controversies, emperor Theodosius convened an ecumenical council in the year 431 at Ephesus which accepted that ‘the virgin Mary gave birth to Jesus as the son of god’. In the proceedings of this council it was further recorded that because of the church built here in dedication to her, she had lived and died here.

The Church of St. John

St. John Who came to Ephesus with the Virgin Mary, assumed following the assassination of st. Paul The authority of all churches under the church of Ephesus as the ‘apostle of Asia’ and continued his mission of spreading Christianity. The church was originally built in the 4th century with a wooden roof on the Ayasuluk hill, where st. John used to live, around the monument erected on the grave where he is believed to have been buried. During the reign of emperor Justinian ‘527-565 ad’, when Ephesus was living through its 3rd golden age, a domed basilica, the ruins of which we see today, was built instead of original church. The Greater part of the edifice was made up of architectural elements borrowed from the older structures of Ephesus. To protect the church against violent Arab attacks in the 7th century, a fortification wall extending to the fortress on top of the Ayasuluk hill was built around it. The Main entrance to the church is through the ‘pursuit gate’ in the south consisting of two tall and thick towers. This Gate opens onto a courtyard called the ‘atrium’. From the courtyard it is entered into the five-domed long and narrow hallway leading to the main-domed church through 3 doors. All of the six domes of this church with naves and cross-shaped plan have completely collapsed. What remained of it to this day, are the thick bearers made of brick and stone and the columns between them. The grave of st. John Is before the apse under the middlemost domed section. It was believed that the dust coming out of a hole in the burial chamber had healing powers. The brick building next to the grave area is a chapel from the 10th century in the middle of which there were priest rooms and baptistery. The restoration work of the Church of St. John, one of the most important pilgrimage places of the christian world since the middle ages, still goes on.

Isa Bey Mosque

The mosque was built by Isa Bey while Seljuk Dynasty ruled here, built and completed in 1375 is an earliest example of ‘Anatolian columned mosques’ the mosque covers an area of 57 – 52 m. Square at the foot of the Ayasuluk hill and the Church of St. Jean. The building consisted of an arcade courtyard and a tripartite mosque chamber with a central double domed roof but the arcades are no longer in evidence. Domes settled on four granite columns and embroidered with faience mosaics and marble stalactic ornamentation. The Original building has two minarets, but only one of them stands still.

The cave of seven sleepers

The story dates back to the 3rd century when emperor Dacius started his ruthless persecution of the Christians who refused to worship idols. According to the hearsay, seven young men who believed in Christ, the protector of the needy and destitute people but couldn’t openly profess their creed, took refuge in a cave they found at the skirt of Panayir Dagi (mount Coressos).one night as they fell asleep the soldiers of Dacius came and closed the opening of the cave with huge rocks. After That night, the seven young men and their dog kept on sleeping deeply for months and years. One morning they were awakened by the daylight which penetrated into the cave after one of the rocks was moved by a shepherd who was grazing his goats under the nearby fig trees. As they were hungry, they sent one of their friends down to Ephesus to bring bread from the bakery. Having descended from the mountain, he was amazed to see motifs of crosses on the pavement as he walked along the marble road. The truth come out when he wanted to buy bread on the market place with the coins of money he had in his possession.

Emperor Theodosius ll having heard about the miracle came down to Ephesus from Byzantium to see the happening. The cave and its environment became an object of attention and reverence as a holy place. As from the 5th century it has become a christian cemetery and religious center visited by thousands of pilgrims until the middle of the 15th century. In the middle of the cemetery there is a basilica. According to the hearsay, the graves of the seven sleepers are located in the basement of the basilica. The only true eyewitnesses of hearsay today are the old fig tree that turn their green leaves to the parching sun.

House of Virgin Mary

The details related with the life of the Virgin Mary could not be brought to daylight despite all the researches made to this day. The virgin Mary had shown extreme care to lead a life of secrecy, leaving to the apostles the mission of introducing the faith of Jesus to the people.

Doubtless, St. John And the Virgin Mary who were entrusted to one another by Jesus before his crucifixion, were obliged to fulfill his last desire. Although he had left the virgin Mary alone, from time to time, in the performance of his apostle duties, the probability of having hidden together in Palestine during their whole life or that he should have left her behind in Palestine is very weak. Moreover, according to writer Eusebio, St. John Had definitely come with the Virgin Mary to Ephesus in Asia towards the year 42. The information about the life and the virgin Mary may be found in some of the verses of the gospel written by st. John For the Ephesians and in the writings of clerical writers who lived between the 1st and 6th centuries. The proclamation of virgin Mary’s divine maternity by the ecumenical council that met in the year 431 in Ephesus confirms that the only church dedicated to the virgin Mary is here or could have been erected here. According to canonical laws in the early ages of Christianity, churches to the memory of saints or martyrs of the religion only, were allowed to be built in their respective locations. Further, it is understood from the council proceedings that the virgin Mary had stayed for a brief period in the location where the church stands today or in a house in its immediate neighborhood and later moved to her house on mount Pion where she lived until the age of 64 and died in the year 46 ad. As Christianity was not a widespread religion in those days, the house where Mary spent her last days was forgotten time went the house of virgin Mary is on the road that stretches from the magnesia gate to mount Pion. Gregoire de Tours is the first clerical writer who mentioned about the small church on the mountain near Ephesus. In 1881 Gouyet, a priest from the Parisian diocese, came to Ephesus to research the truth about the house mentioned and described in the book“ the life of the Virgin Mary“ written by Anna Katherine Emmerick, a German (1774- 1821) he proceeded to Ephesus from where he sent reports to the authorities in Paris and even in Rome, stating that he had found the house. However, his reports were not accepted. Ten years later, Eugene Pauline, a Lazarist priest who was the president of the Izmir french. College, entrusted two priests and catholic officials with the search of the house. On the day of 29 July 1891, the group after a long march arrived tired and thirsty at a table land in the mountain covered with tobacco fields. When they asked for water from the peasants working in the field, the peasants pointed at a ruined house, called monastery where they could find water. When they got there, they met with the house of virgin Mary on a slope from where the scene of the Ephesus city and the sea could be seen just as described by Katherine Emmerick. Between 1892 and 1898, two faculty members from the french college in Athens who came to the site, realized the structure was an ancient and significant relic and determined that its ruins were dating from 1st century. In conclusion, with the visits paid by pope Paul vi in 1967 and papa john Paul II in 1979 to Ephesus and the majestic holy masses held on the occasion of the visits, the belief that the virgin Mary had lived and died in Ephesus gained strength in the Christian world. The belief in the virgin Mary is the most manifest among all the beliefs in heavenly personalities in Ephesus, which originated with Artemis and evolved in the course of history. The Ephesians, who at the beginning opposed the preachings of St. Paul In the Theater of Ephesus, carried over all the traits of the great goddess they used to believe in and worship to the virgin Mary who appeared before them everywhere and whom they glorified after Artemis was prohibited to them.

Whether her coming to Ephesus and her life and death at the place of worship on mount Pion is a true happening or not, the image of the Virgin Mary is closely related with Ephesus.

Ephesus Museum

The ongoing excavations in Ephesus, which initially began in 1869, have only uncovered a small fraction of the ancient city, amounting to just one tenth. It is unfortunate that a portion of the artifacts unearthed before the foundation of the Republic of Turkey now adorn the halls of prominent museums in Europe.

The Ephesus Museum was established in 1929, initially serving as a repository for all the relics discovered during excavations or brought in from the surrounding areas. However, it was not until 1964, upon the completion of the southern section of the building, that these relics could finally be put on public display. As the number of artifacts continued to increase due to ongoing excavations, the need for an expanded exhibition area became apparent. Consequently, the northern section of the museum was constructed in 1976, bringing it to its present state.

Today, the Ephesus Museum stands as a treasure trove of remarkable finds, most of which were obtained from excavations conducted in Ephesus itself, as well as from the Church of St. John, the Belevi Mausoleum, and nearby ancient settlements. These artifacts hold great significance for the archaeology of Ephesus and Anatolia as a whole. Each relic receives careful attention and protection, followed by documentation through drawings, photography, and inventory work. Depending on their significance, they are either showcased in the museum or safely stored for future preservation.

Sirince Village

Sirince, located 8 km away from Selcuk, is an ancient Greek village nestled at an altitude of 350m. Its rich history dates back around 5,000 years. The village’s appeal as a settlement stems from its mountainous terrain, which acts as a natural fortress safeguarding it from potential threats, as well as its fertile land and abundant water resources, making it ideal for agriculture. The agricultural products of Sirince include vineyards, olives, peaches, apples, walnuts, figs, and a small amount of tobacco.

During the 1950s, tourism began to flourish in Sirince, leading to a significant increase in the local population, reaching 2,000-3,000 residents. However, over time, the population gradually declined to around 700. Nevertheless, Sirince experienced another surge in population when it became an attractive destination, especially for retirees seeking a tranquil lifestyle away from bustling cities. To this day, you can still find old Greek houses in Sirince that have been transformed into charming guesthouses or pensions. Additionally, Sirince is renowned for its delightful assortment of wines, adding to its appeal among visitors and wine enthusiasts.